Intro

I joined Amazon on September 1, 2022 — and today celebrating my 3 years of Day 1’s 🎉. These 3 years have been AWSome — full of growth and valuable experiences, some shaped by lessons learned from mistakes.

On this day, wanted to write a quick article on the most important lessons I learned along this journey so far.

Learn more about Amazon’s Day 1 culture here.

The top 3 lessons

Guardrails > processes relying on hope

Don’t just hope people do the right thing — build systems that make it hard to do the wrong thing.

Before Amazon, I used to write the code, create a pull request, get it reviewed by a peer, merge, and throw the task to a team of QA engineers, hoping they will find the issues for me. Looking back, this is how I saw processes being hoped to work, bugs hoped to be caught, deployments hoped to be safe, etc — everyone did their best, tried hard not to make a mistake, and usually there was no issue — until there was.

However, all relying on hope rather than guardrails. Hopes do not work because: 1) they don’t scale as you grow, 2) they are expensive, 3) they are forgotten.

A guardrail is a built-in, automated verification of a system that prevent mistakes before they happen. Guardrails ensure consistency and reliability while letting teams move fast.

They can come in different forms depending on the context and are already well-known in the modern DevOps world. It is only the question of identifying the manual processes and hopes and replacing with the right automation.

Some examples:

Automated unit and integration tests

- Manual process risk: QA engineers are supposed to test every change, and perform regression tests time-to-time. Both are very expensive.

- Guardrail: Instead engineers need to own the feature in full. Automated test coverage should always be part of the Acceptance Criteria. While there is some upfront cost in the short term, this will enable almost free product quality assurance and confidence in the long term.

Automated CI/CD pipelines

- Manual process risk: Engineers are supposed to follow a multi-step deployment checklist. One missed step can cause customer impact.

- Guardrail: Automated CI/CD pipelines enforce checks (e.g., run tests, validate configs) before deployment, preventing human error.

Automated Monitoring

- Manual process risk: Engineers are expected to notice performance issues manually or from customers.

- Guardrail: Set up alarms with good latency thresholds before customer workload is impacted.

Code quality / reviews

- Manual process risk: Engineers are expected to catch all style or safety issues in code reviews.

- Guardrail: Linters, static analysis, or automated security scans catch errors automatically, ensuring consistency. This will enable engineers focus only on things without noise and preventing unnecessary nit-picks.

Prove assumptions. Early.

At Amazon, writing is a core part of engineering, and as engineers we write a lot of design documents.

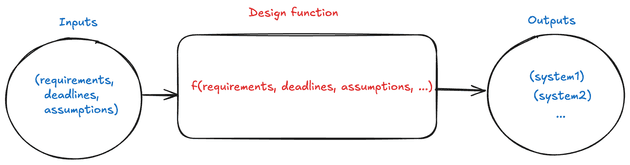

I learned to look at a system design this way: we are searching for a Design function that takes a point (requirements, deadlines, assumptions, …) from a set of inputs () and produces an output system from a set of systems (), mathematically:

Equation 1: Design function definition

Graphically,

I learned that the most tricky, and extremely important parameter from the inputs to this function is the assumptions. Usually assumptions stem from the status quo in a team, old tribal knowledge that everybody believes is true, but nobody actually has proven it.

Two years ago, I worked on a project to cut infrastructure costs tied to an expensive caching data store. My initial assumption was that we were caching unnecessary data, so I drafted a complex system to fix it. For two weeks, I went back and forth with senior engineers, defending the design — until they pushed me to dig deeper into the metrics.

In just one day of analysis, I realized my assumption was wrong. The entire design was obsolete.

As we saw in equation 1, if one parameter — like an assumption — changes, the output system must change too!

The takeaway? If I had spent that one day proving my assumption early, I could have saved weeks of wasted effort.

What you work on ≥ technical complexity

As engineers, it’s tempting to look for hardest technical challenges, at least this is what I used to do in the beginning of my career. Looking back, I think that urge came from a place of still building my technical skills (and being surrounded by peers doing the same). Solving a coding problem nobody else around could used to bring recognition. Promotions were often tied to how many languages and frameworks you knew — and how deeply you knew them. For example, in a promotion assessment you might be asked a JavaScript question like:

Can you explain how the event loop prioritizes microtasks vs. macrotasks, and how that impacts async/await execution?”

Back then, your chances of being promoted could depend on how well you answered questions like this. If you could walk through the details — that promise callbacks run in the microtask queue before timers in the macrotask queue — you were seen as ‘senior enough’. If not, your promotion might be delayed, regardless of whether the work you delivered created real customer impact.

At Amazon, I’ve seen a very different approach. Guided by the Leadership Principle Hire and Develop the Best, the company focuses on bringing in top engineering talent from around the world — and then helping them grow even further. Every Amazonian engineer is a strong coder — so you can’t stand out just by writing good code or tackling technically difficult problems. And every engineer I’ve worked with is among the most hardworking people I’ve ever met.

So, if technical skill and hard work aren’t enough, what really sets you apart? This is what I have learned:

- Focus on impact. Work on projects that deliver meaningful value to the organization and customers, not just the ones that are technically challenging.

- Tackle complexity beyond code, end-to-end and independently. Navigate ambiguity, clarify unclear requirements, coordinate across teams, and drive projects forward when the path isn’t obvious: without being told.

These are the things that make you stand out — and the work you get promoted for.

Conclusion

These are just a few drops from the ocean of lessons I have learned over the past 3 years at Amazon. I’m excited for what’s ahead at Amazon and look forward to sharing more lessons when I celebrate 4 years of Day 1 next year 🙂